| With a Print & Full Archive Subscription, you'll have exclusive access to more than a century and a half of groundbreaking articles by leading experts in their fields. This November brings the midterm elections to the U.S. It’s a fine opportunity to reflect on science, its value to society and why there are anti-science trends worldwide—and have been for a long time. Also, on November 11, 1918, the Great War (WWI) dragged to an end, much to the relief of weary millions; here’s a nod to that centenary. Finally, we revisit a concept that once seemed ridiculous: Can continents drift around the earth like leaves on a pond? It can take a few million years, but yes, they can: in the 1960s continental drift was proved true. | | | .jpg) “Claims of supernatural phenomena” include this girl from Soviet Georgia and her supposedly magnetic abilities; August 1991. “Claims of supernatural phenomena” include this girl from Soviet Georgia and her supposedly magnetic abilities; August 1991. | | | Science is great. Sometimes it isn’t. The backlash has produced some strange anti-science trends during the Age of Reason, including criticisms and outright rejection. - June 1934: Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace castigates scientists for following curiosity but not prioritizing the greatest good for the greatest number.

- August 1991: The Editor of the Russian edition of Scientific American weighs in on “Antiscience Trends in the U.S.S.R.” (the Soviet Union, as we used to call it).

- November 2016: Not just science: reality and facts seem to be under assault. There are, however, “Five Things We Know to Be True.”

- July 2018: Psychological scientists critically examine anti-science thinking and come up with strategies to overcome cognitive biases underlying irrational decision making.

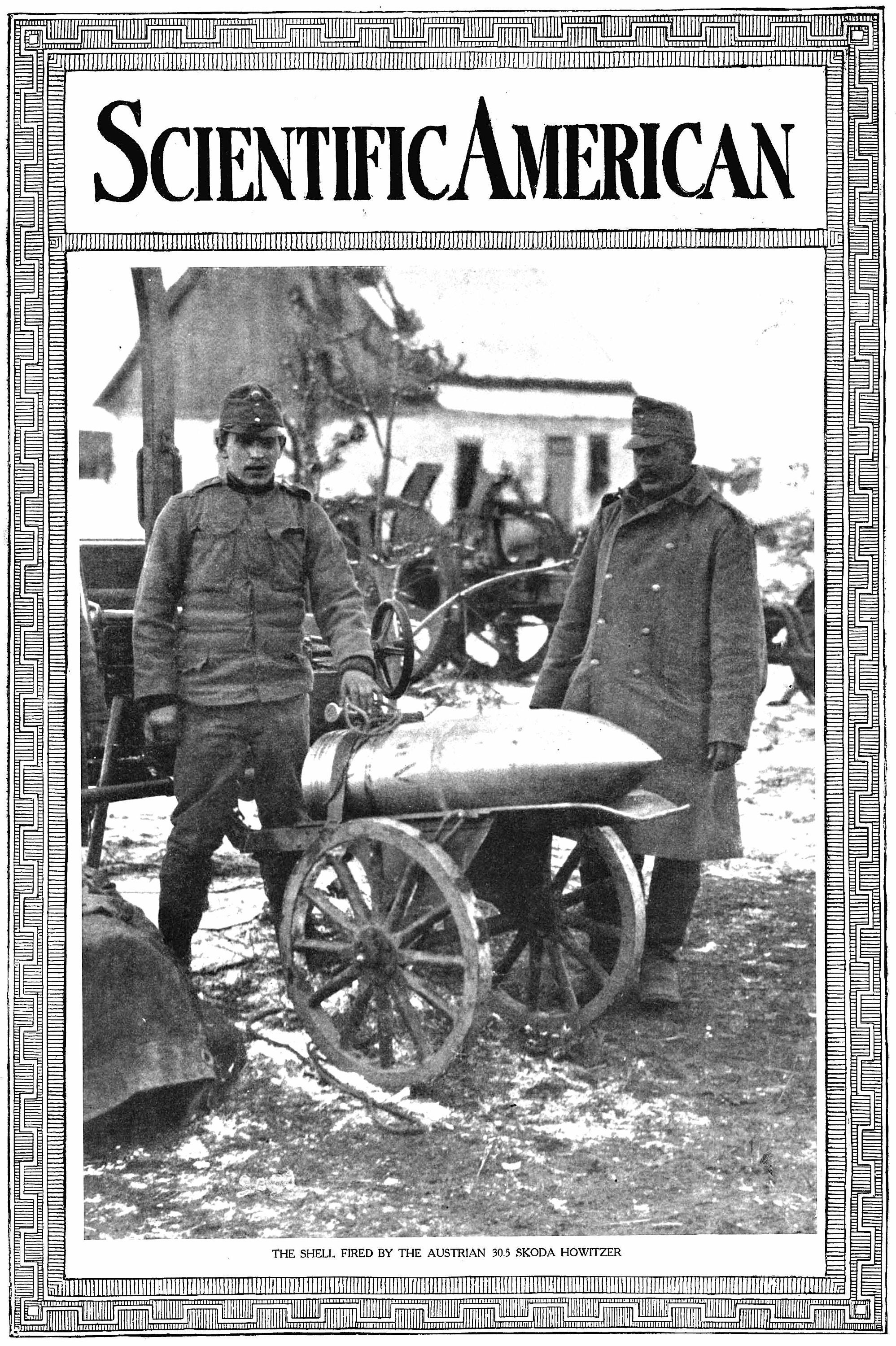

| | | | |  Two weary Austrian artillerymen and their burden, a 12-inch shell for a Skoda gun, 1915. Two weary Austrian artillerymen and their burden, a 12-inch shell for a Skoda gun, 1915. | | | This magazine covered the First World War extensively: the science of weapons and warfare, the wounded, the destruction, the wholesale diversion of economic activity to support the war effort, and the social upheavals that accompanied all of these. - April 1915: This war of artillery increased in size, scale, industrial production and destructiveness, as epitomized by this sole cover image.

- September 1915: Casualties were unprecedented. An article on the Hindenburg House in Königsberg covers efforts to give permanently disabled veterans some mobility.

- February 1917: “Women in Industries: How Far Can She Go?” The expanding industrial capacity relied heavily on women, with some worries as to the future of the social fabric.

- November 1918: The “wave of hysterical rejoicing” at the Armistice and the arrival of peace obscured the complexities of the war’s cause, and instead blamed only Germany.

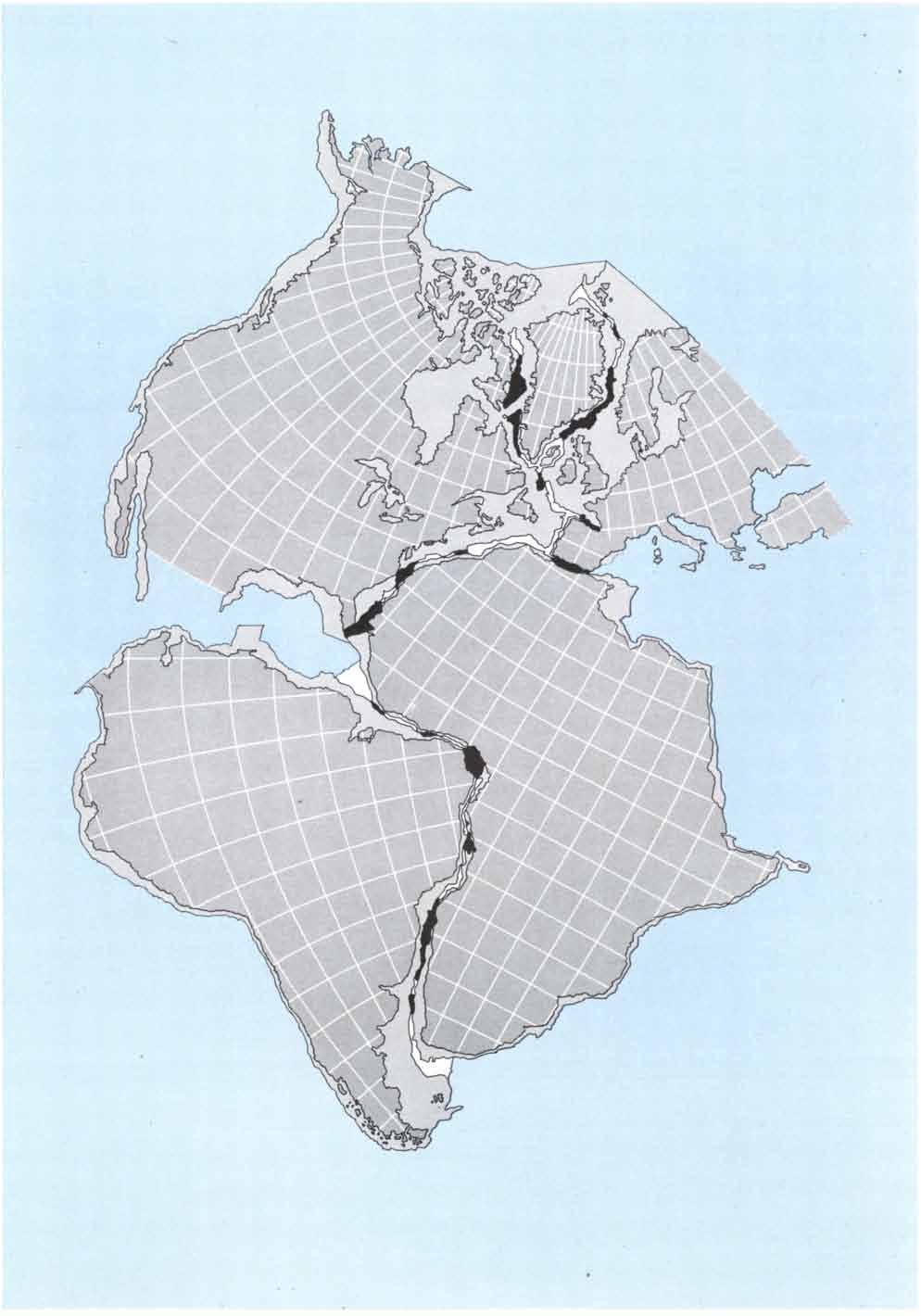

| | | | |  Continental jigsaw, put together along the edges of the continental shelves. Continental jigsaw, put together along the edges of the continental shelves. | | | The remains of tropical plants in northern regions had people speculating on continental drift in the 19th century—we have an article from 1855 that fell somewhat flat—but it was not until the 1960s that the immense time span was understood and the concept was considered proved. - December 1855: “Pole-changers” were ridiculed: If Earth were 9,000 years old, England would have had to drift north at 2,024 feet a year.

- January 1926: Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift, “seems absurd. It may prove to be erroneous. It may gain final acceptance among geologists.”

- April 1968: “The Confirmation of Continental Drift”: Gondwanaland, Laurasia, and us.

- July 1988: Not just once, it’s a cycle: data show the supercontinents have joined up and split apart a few times in the past billion years.

| | | | | | Learn while you sleep. It’s a tempting concept, but is it real? Yes: our brains remain highly active while we slumber, and it is possible to control the memory process to some degree.

Plus: a special report on the science of inequality For more highlights from the archives, you can read November's 50, 100 & 150 Years Ago column. | | READ THE ISSUE |

Enjoy the journey!

Dan Schlenoff, editor of “50, 100 & 150 Years Ago” | | | | | | | |

Comments

Post a Comment