| | | Dear Friend of Scientific American,

Do you ever feel physically uncomfortable from unwanted noise? A bunch of new research shows that noise is more than just annoying – it can be dangerous. It's been linked to heart disease, sleep disruption, learning delays and of course hearing loss. We hope our graphics-rich feature on noise and health will help advance policies to reduce noise. Relatedly in this issue, we advocate for making cities more pedestrian-friendly (and less clogged with honking cars) and share the health benefits of spending time in nature. I hope you're enjoying a lovely springtime and are able to enjoy some peace and quiet outdoors.

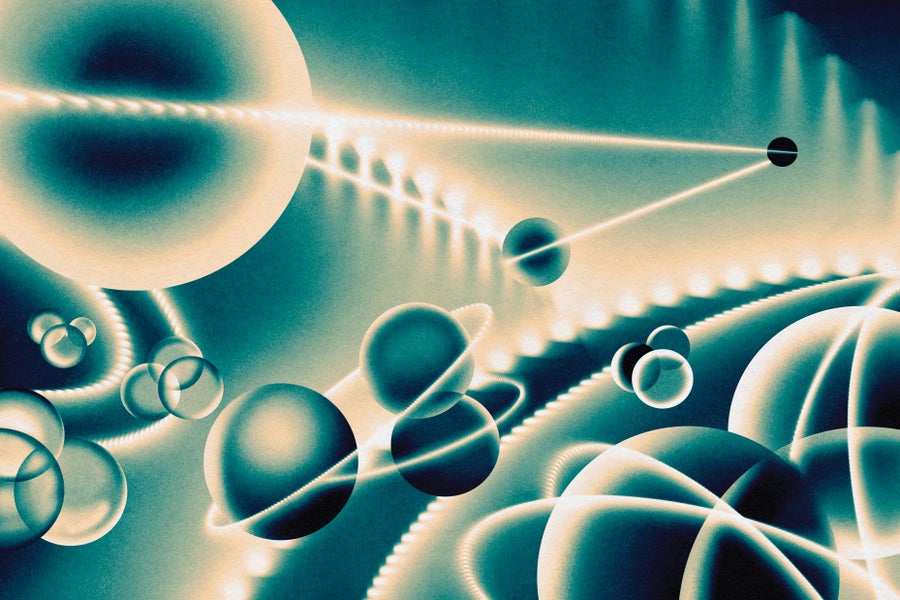

The strongest force in nature is the strong force, which keeps the quarks and neutrons and protons in atomic nuclei stuck together. It's also one of the most mysterious forces in nature, but physicists are finally starting to understand how it works. They're starting to measure just how strong it is (strong!) and how it falls off with distance. Three leading strong-force researchers explain how they've been able to test the strong force and describe the particle that carries it, the gluon.

Many of us at Scientific American are birders, and we love sharing stories about how parrots are taking over the world, how birds use quantum physics to migrate, how they flutter their wings at their mates to say "after you," and why they have such skinny legs. In the May issue, a natural history researcher explains how feathers evolved and how they are specialized for different types of flying, feeding, hunting and showing off. I hope you are enjoying spring migration if you are into birds – and if you're not a birder yet, this is a great time of year to start.

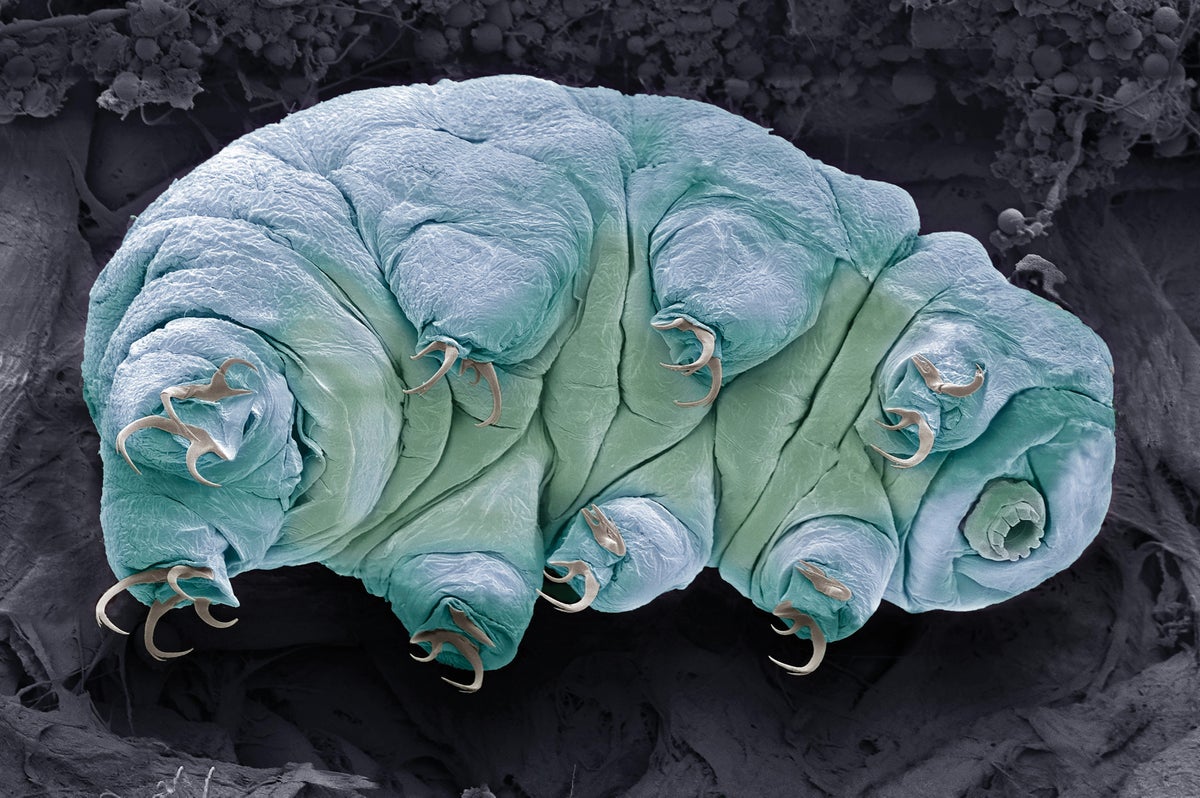

We are living in the pyrocene, the great age of fire. Here's how humanity shaped fire and fire shaped humanity across millennia, from our digestive tracts to our energy grids. Finally, tardigrades are some of the quirkiest and most robust animals in the history of life on Earth. They're basically indestructible (they've lived through exposure to space) and researchers just discovered one mechanism these adorably pudgy "water bear" creatures use to go into deep hibernation, almost like a fungal spore, to withstand any threat. Thanks for your support of Scientific American, and we all hope you enjoy the May issue.

Laura Helmuth

Editor-in-Chief

Scientific American | | | | | | | | | May Issue Highlights | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | Read the latest issue! | | How fire forged human civilization. | | | | | | | | | |  | |

To view this email as a web page, go here.

You received this email because you opted-in to receive email from Scientific American.

To ensure delivery please add chiefeditor@scientificamerican.com to your address book.

Unsubscribe Email Preferences Privacy Policy Contact Us

Comments

Post a Comment